Armenian Church of the Holy Resurrection in Old Dhaka is one of the key tourist attractions of Dhaka City. Constructed in the late 18th century, this quiet little church in Old Dhaka bears the testimony of a large Armenian community in Dhaka.

Armenians played a significant role in Bengal trade and commerce in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They had established settlements in Hughli, Chinsura, Saidabad, Murshidabad, Kasimbazar, and other Bengal business centers, including Dhaka. Although they are entirely gone now, the little church they built in Dhaka still exists.

Table of Contents

- The Armenian Community in Dhaka

- The Trade of the Armenians in Bengal

- The Decline of the Armenians in Dhaka

- The Construction of the Armenian Church in Dhaka

- The Plan of the Armenian Church in Dhaka

- The Armenian Church of Old Dhaka in Present Days

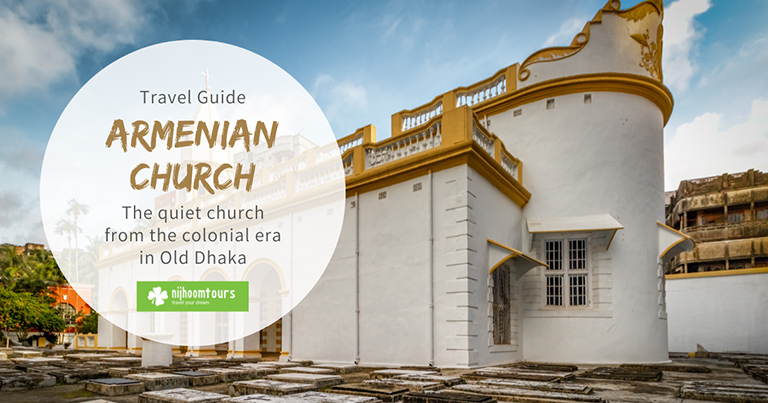

A full view of the Armenian Church in Old Dhaka. ©Photo Credit: Raw Hasan

The Armenian Community in Dhaka

The Armenian diaspora began when the Safavi rulers of Persia conquered their homeland, Armenia in Central Asia, in the sixteenth century. To achieve political and commercial objectives, Shah Abbas I transplanted Ispahan and New Jalfa about 40,000 traders specialized in inter-Asiatic trade.

The Armenians first came to Bengal from these two trade cities, following the Persian adventurers’ footsteps. Initially, they did business in Bengal on behalf of their Persian masters. Over time, they had formed their community in Bengal.

They named their Dhaka settlement Armanitola, meaning the Armenians’ habitat, a place name still there in Old Dhaka to announce their eventful presence. They were patrons of education. Nicholas Pogose founded a school in Dhaka, which was named after him and still exists.

A front view of the Armenian Church in Old Dhaka. ©Photo Credit: Raw Hasan

The Trade of the Armenians in Bengal

Armenians were skilled tradesmen. They played a significant role in Bengal trade and politics from around the early seventeenth century. Their presence was a common feature in all the vital trade and manufacture centers, cities, and ports.

All European Companies in Bengal used to engage Armenians to represent them and their cause to the court. All the nawabs are known to have involved Armenian merchants in transacting their businesses openly or clandestinely. Khojah Petrus Nicholas, the Armenian community leader, was a financier and court advisor to Nawab Alivardi Khan.

Khojah Wajid was one of the three merchant princes (the others being the Jagat Sheth and Umichand) who collectively dominated the economy of Bengal in the last three decades of the first half of the 18th century. He had a monopoly in the salt trade at that time. Armenians were also engaged in the jute and skins trade.

The dome of the Armenian Church in Old Dhaka. ©Photo Credit: Raw Hasan

The Decline of the Armenians in Dhaka

The Armenians’ assertive presence in Dhaka began to decline from the beginning of British rule following their conquest of Bengal in June 1757. Many Armenians gave up trade and commerce for land control and bought extensive zamindaris (feudal land-ownership) in eastern Bengal after the permanent settlement.

In the nineteenth century, they started going back to Central Asia and Iran with their great wealth amassed in Bengal. Many of them also went overseas to invest their capital in plantations in partnership with their European counterparts.

Though their absolute number declined in consequence, their presence in eastern Bengal trade, particularly in jute and skins, remained articulate down to the end of the century. The Armenian families who entered land control gradually shifted their interest to other businesses, such as banking, export trade, and agencies to exporters and importers.

The construction year written in the Armenian Church in Old Dhaka. ©Photo Credit: Raw Hasan

The Construction of the Armenian Church in Dhaka

In faith, the Armenians were Christians belonging to the Greek or Orthodox Church. They built churches wherever they settled.

The early Armenian settlers built a small chapel amid their community graveyard in Armanitola. By the end of the 18th century, the Armenian community had grown considerably, and the chapel was found inadequate for the community’s needs.

So the chapel was replaced by the Holy Resurrection Church with significant donations by Agah Catchick Minas, who donated the land, and Michael Sarkies, Astwasatoor Gavork, Margar Pogose, and Khojah Petrus for construction costs.

Before this church had been built, the Armenians were interned beside the Roman Catholic Church at Tejgaon. The church was completed in 1781 and consecrated by His Grace Bishop Ephreim.

In 1837, a clock tower was erected on its western side. Allegedly, people could hear the clock from four miles away and synchronize their watches with the tower’s bell sound.

The clock stopped in 1880, and an earthquake destroyed the tower in 1897. In 1910, a parsonage and electric lights were added, and the floor was decorated with marble, which was a donation by Arathoon Stephen of Calcutta.

Corridor of Armenian Church of Holy Resurrection at Old Dhaka ©Photo Credit: Raw Hasan

The Plan of the Armenian Church in Dhaka

The plan of the Armenian church is rectangular. Features include an arched gate and an arched door. There are a total of four doors and 27 windows. The main floor is divided into three parts: a pulpit enclosed by railings, a middle section with two folding doors, and an area separated by a wooden fence for seating women and children. There is a spiral staircase in the church.

In the old graveyard, among the 350 people buried there, a statue stands at Catachik Avatik Thomas’s grave, portraying his wife. The statue was bought from Kolkata, and the grave is inscribed with the words “Best of Husbands.”

Statue on a grave at Armenian Church of Holy Resurrection in Old Dhaka. ©Photo Credit: Raw Hasan

The Armenian Church of Old Dhaka in Present Days

Today, the Armenian church in Dhaka is usually closed. The last Armenian who used to take care of the church is Mikel Housep Martirossian (Micheal Joseph Martin). He kept the centuries-old births, deaths, and marriages register and looked after the ancient tombstones that chronicle the history of the Armenian community in Bengal. He was also one of the Armenians who were in the jute trade. You can read the story of how he saved the church from being extinct in his own words.

Martin retired and spent his final few years in Canada with his three daughters and grandchildren before passing away in 2020 at 89 years of age.

The Armenian Church of Old Dhaka has been the subject of the BBC and AFP documentaries and has received recognition from the Bangladesh government as an archaeological site under the Department of Architecture.

Have you ever visited the Armenian Church in Dhaka? How amazing have you found it? Please share your experience with us in the comments!

You might also be interested in reading 17 Best places to visit in Bangladesh not to miss and 101 Things to know about traveling to Bangladesh.

Check out our Old Dhaka Tour to visit the key attractions of New and Old Dhaka, including Armenian Church. The full-day tour starts from $70* US with an air-conditioned car, English-speaking guide, all entrance tickets, lunch at a local restaurant with authentic Bangladeshi food, a rickshaw, and a boat ride.

Check out our 1-7 days Bangladesh tour packages and 8-28 days Bangladesh holiday packages to visit Bangladesh with comfort.